Born in 1885 in Budapest, Hungary, György Lukács was a radical, Marxist, Jewish thinker whose biography and theory can inspire us today to conceive of a more ethical world.

The life and work of György Lukács has much to teach us today. A radical thinker who was demonized both during his lifetime and posthumously from all sides of the spectrum, Lukács believed in a new age of ethical action. Such an age has yet to come, and many of the philosophies for which he advocated, such as anti-capitalism and anti-modernism, continue to be condemned. Still, many of the concepts he heralded such as transcendental homelessness – the longing and ability to be at home everywhere – remain evermore prescient amid continued immigrant crises and climate displacement. In bringing his story close to us in 2020, we have a chance to consider how we might work to bring about a future of mass ethical action.

Lukács was born on April 13, 1885 in Budapest, Hungary to a Jewish family. An influential banker, his father Jozsef Lowinger, in an assimilatory effort, changed their surname to the more Hungarian “Lukács” in 1890. Even at a young age, Lukács was publishing reviews of theatrical productions in the Hungarian press. He began his higher academic studies in Budapest, receiving a Ph.D. in Political Science from the University of Kolozsvar in 1906, and later another doctorate in Berlin. In 1908 he received attention for his collection of essays on literary criticism titled Soul and Form (first published in Hungary and later republished in Germany in 1911). In Soul and Form, Lukács theorized that form is the condition through which expression communicates the will of the creator within the social conditions they are working in. Also in 1908, he founded a theater devoted to the production of modern plays and published The History of the Development of Modern Drama. Many of his early works at this time were deemed too German and philosophical by the Hungarian literary elite. It is worth noting that it was also at this time that he renounced his Jewish heritage.

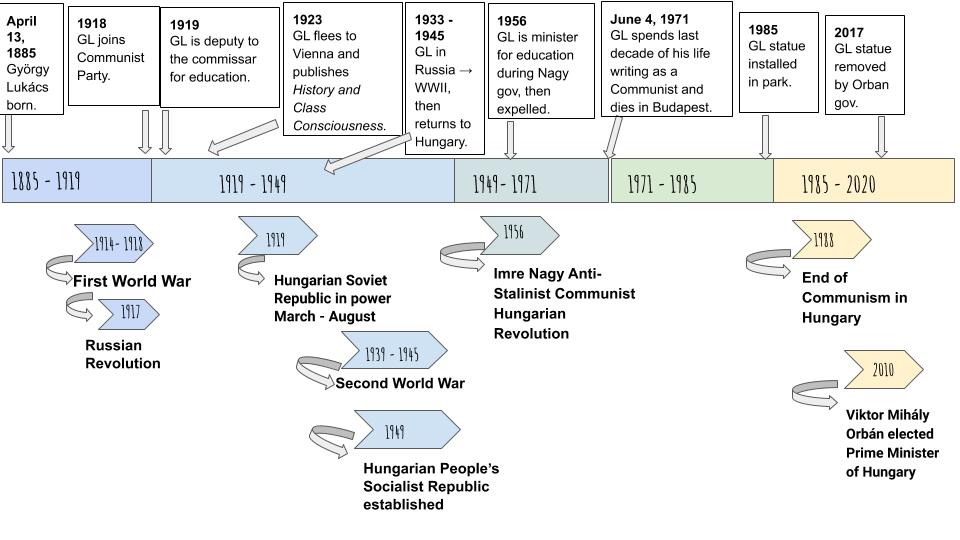

Just before the eruption of the First World War, Lukács published The Theory of the Novel (1914-15), in which he wrote of Fyodor Mikhailovich Dostoevsky’s novels as heralding a new age and first theorized transcendental homelessness. Feeling motivated by the cause of the proletariat, and the promise of a brighter future, Lukács joined the Communist Party of Hungary in 1918. At the time he stated, “Liberation from capitalism means liberation from the dominance of economics.”

During the Hungarian Soviet Republic’s control of the country between March and August of 1919, Lukács served as the deputy to the commissar for education. As the deputy commissar, he nationalized all theaters, staged a public exhibition of formerly privately owned and treasured artworks, gave teaching positions to academic radicals, translated famed literary works into Hungarian, created mobile libraries and proclaimed, “culture is the rightful due of the working people.” When the Hungarian Soviet Republic collapsed, Lukács hid underground organizing and fearing for his life, ultimately escaping to Vienna in 1919. In exile in Vienna, Lukács married and was highly influenced by his fellow Hungarian Communist Party member Gertrud Bortstieber. At this time he read the work of Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel, Karl Marx and focused on working through Leninist philosophies which resulted in his 1923 publication of History and Class Consciousness and one year later, Lenin: A Study on the Unity of His Thought.

In History and Class Consciousness Lukács, like Marx, studied the process of reification – wherein humans become objects through labor. Lukács believed in human creativity and saw workers being turned into objects while laboring as a form of rationalized violence. Capitalism portrays its ordering of our world as natural, but in reality this order is entirely constructed which means it can be unmade. Class consciousness is the need for the proletariat to understand and internalize their subordinate position and in so doing, be able to free themselves intellectually from it. Lukács believed that working through politics philosophically was the only way to achieve intellectual freedom. In the words of Daniel Lopez, so that “we may consciously and knowingly use theory, and not be used by it.”

In the 1930s, Lukács was summoned by Soviet leadership and moved to Moscow where he held a position at the Marx-Engels Institute and faced widespread criticism. Theorists such as Theodor Adorno, Louis Althusser and Jurgen Habermas all condemned him for what they saw as his promotion of an authoritarian form of Leninism which tried to reduce all objectivity to subjectivity. Lukacs himself even publicly retracted some of History and Class Consciousness to more fervently align with Stalinist orthodoxy. In 1944 he returned to Budapest to take a professorship at a local university.

In 1956, the Hungarian uprising offered a new opportunity for Lukács. During the brief Imre Nagy government, Lukács served as the minister for education. After Stalin’s death, he could openly criticize Stalinism and more fervently support a different future for Marxism. When the Soviet Union invaded, he was imprisoned in Romania. Luckily, he was not executed and just expelled from the communist party. In the 1960s, the final decade of his life, Lukács worked on Specificity of the Aesthetic (1963), rejoined the communist party and continued to publish extensively on Marxist ethics, literature and art. He died on June 4, 1971 in Budapest. As a multi-faceted outsider and radical thinker who witnessed and participated in some of history’s most profound revolutions, his memory inspires both awe and fear. While Viktor Orban’s nationatlist government condemns his legacy, around the world he has reached newfound popularity and is both well read and respected, if not still uncomfortably complex for some.

Author: Emily Shoyer is a specialist in modern and contemporary art, with a focus on memory and trauma through a decolonial and psychoanalytic lens. She has published and spoken internationally on modernist postcolonial and global diasporic contemporary art and has held curatorial and research roles at Venus Over Manhattan, the Museum of Modern Art and the 9/11 Memorial & Museum. She holds an MA in Modern & Contemporary Art History from the Institute of Fine Arts, NYU and a BA in Art History from Barnard College, Columbia University.